What is Cognitive Ergonomics and Why Does It Matter?

What opportunities and risks should companies consider when workplace tool adoption is influenced by broader societal trends?

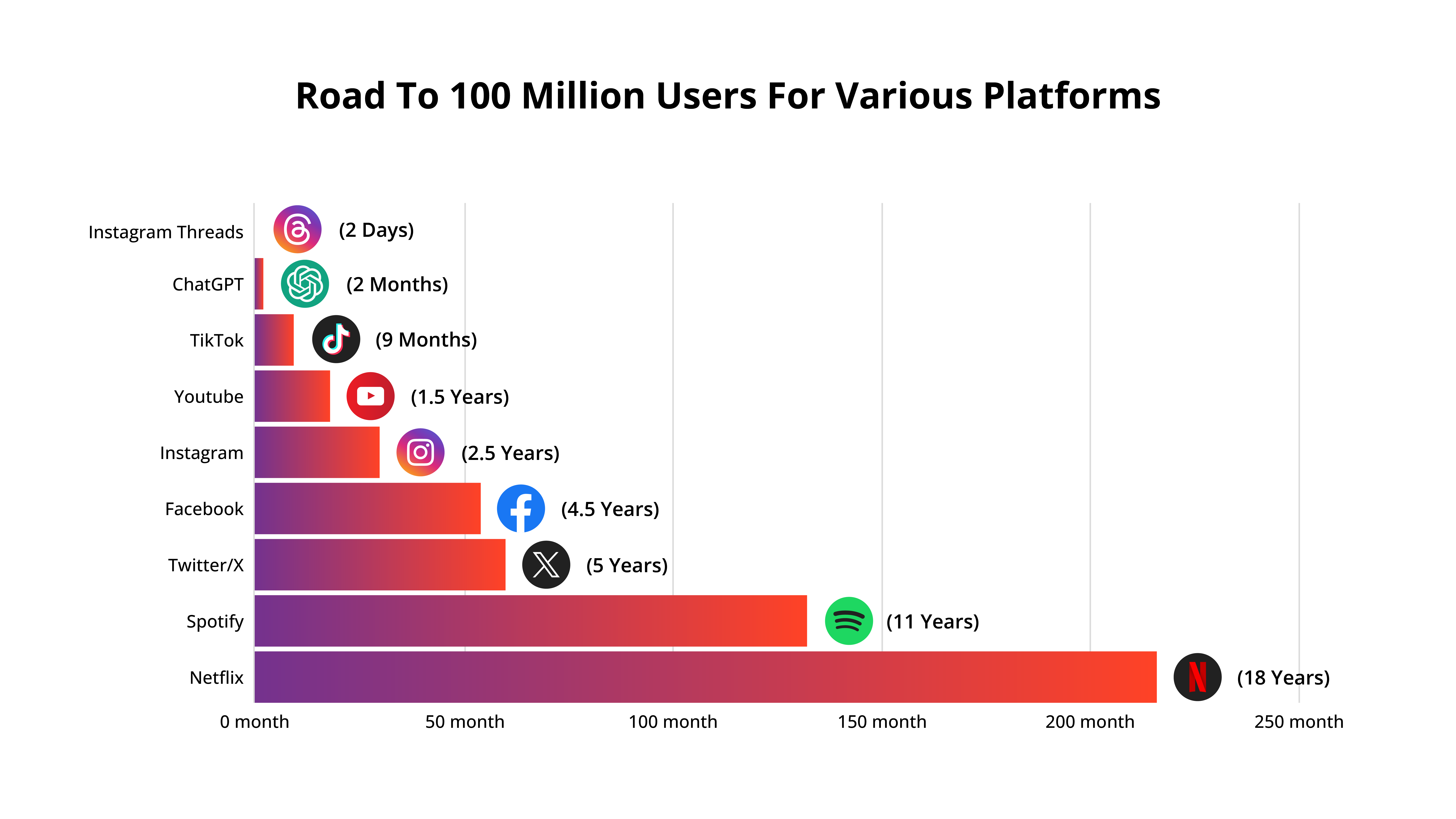

There is a statistic that most have encountered at least once: the time it takes for a platform to reach 100 million users.

ChatGPT Statistics | © Copyright, Source: demandsage

Exponential growth is not a universal rule for every new platform, but for a select few, it is (see image). What changed between Netflix, Facebook, and ChatGPT? Why did TikTok take six times less time than Facebook to reach 100 million users? And how did ChatGPT accomplish this milestone in just two months?

A partial answer lies in cognitive ergonomics—the ease with which an object, physical or virtual, can be adopted by the human brain and subsequently used efficiently and effectively. Netflix debuted as the first subscription-based streaming platform, a markedly different adoption challenge from TikTok, which emerged in the wake of the social media explosion led by Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter (now X). By the time TikTok arrived, the human brain was already accustomed to social communication structures—mentions, connections, profiles, and news feeds.

A similar argument applies to ChatGPT, though its resemblance is not to previous interfaces or technologies, but rather to the very first technology available to humans: language. While AI has been evolving in research centers since the 1950s, experts have long emphasized the existence of an AI that is cumbersome, complex, and far removed from everyday use [1]. The interfaces of GPT, Midjourney, Claude, Gemini, and others, however, are so immediate and cognitively ergonomic that their adoption is not only nearly instantaneous but also seamlessly integrates into daily routines. [2]

In a conversation with Massimo Lupi, Professor of Learning & Development at the University of Milan and Organizational Behaviour at GSOM at the Polytechnic University of Milan, we reflected on the radical transformation of personal computers in the 1990s. [3] The true revolution was not merely the compact and manageable size of the machine, but the shift from requiring programming knowledge for even the simplest tasks (such as creating a text document) to the ability to simply click on the Word icon and open a blank page for writing. This is the key transition: behind the Word icon, the machine’s complexity is hidden from the user. The user does not need to understand the algorithms triggered by a click; they only need to know how to type on a QWERTY keyboard (which emerged as the most cognitively ergonomic for machine-based writing) and how to select icons to modify font, colors, and formatting.

Such changes are not exclusive to contemporary technologies—they are simply occurring at a faster pace than in the past. How many of us understand the intricate workings of an internal combustion engine when driving, or know how to start a fire in nature while using a stovetop to make morning coffee? Whether physical or virtual, interfaces conceal complexity, making the use of objects and technologies ergonomic. This is precisely what ChatGPT represents.

A second trend is intertwined with this transformation: the speed of adoption, the continuous sharing within virtual networks that expands our lived experience, and the technological hype cycle (as famously outlined by Gartner). These dynamics render the relationship between technology, workers, and companies more unstable and complex. It is the “pop transformation” of technology. Discussing this phenomenon on Nova24, a blog by colleague Marco Minghetti, [4] within a broader reflection on “pop management”—a trend reshaping the relationship between companies, managers, and employees—we noted how pop technologies are fundamentally altering the questions employees ask of their companies.

Let us explain.

It is no longer companies that dictate which tools should be used; rather, it is the collective workforce that demands companies change the way they operate. This shift has already occurred in synchronous and asynchronous work, from video calls to Teams, chats, and online communities that resemble social networks more than traditional enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems or email threads (Facebook’s failed attempt at launching Workplace—a corporate version of Facebook—is a case in point). It is not just the mode of work that is changing under the influence of social and cultural shifts over the past decade, but also the technology itself. According to a recent study by Microsoft and LinkedIn, by 2028, 86% of employees will use AI tools at work. Already today, 75% do so [5] often outside corporate-approved frameworks (with implications for security, privacy, and data management). This is the phenomenon of “Bring Your Own AI” (BYOAI), a concept already solidified through the use of generative AI tools. In short, while in the latter half of the 20th century, companies imposed cultural models, today it is society that imposes its frameworks onto companies. In this sense, the trend is distinctly pop.

How does OpenKnowledge support companies (complex organisms composed of people, cultures, management structures, ideas, projects, and objectives) in navigating these challenges?

First and foremost, we advise against trying to stop the wind with one’s hands. Preventing the development of habits, cultures, and working methods—unless they have a direct and measurable impact on financial goals—is rarely a good idea. The effort required to change societal habits is costly in terms of cognitive and political capital. Outright rejection of a phenomenon such as generative AI in the workplace may prove counterproductive, even in terms of fostering experimentation, innovation, and entrepreneurship.

We advocate for guiding and enabling rather than policing and controlling. While the BYOAI phenomenon may compromise corporate data security and introduce risks in processes, banning it outright is not the solution. Instead, the most effective approach involves studying it, steering it, and training employees on its proper use within corporate sensitivities and requirements. This method yields the greatest long-term benefits.

Finally, we help companies anticipate trends. Though it may sound like an obvious truth, social and cultural trends serve as powerful predictors of employee demands within organizations—whether those demands pertain to aspirations, social concerns, or the adoption of specific technologies and work methods. In this regard, traditional market intelligence, which focuses on identifying technological and innovation trends, should evolve into social-cultural intelligence. This approach enables companies to understand deeper, latent needs that will have the most profound and lasting impact in the medium to long term.

Sources

[1] I recommend reading an interview from a year ago with Stefano Quintarelli—entrepreneur, investor, and former MP—published on Wired: “Why the AI to Watch Is the ‘Boring’ One,” Wired, February 26, 2024. Intelligenza artificiale: tenete d’occhio quella “noiosa” | Wired Italia

[2] A clarification: Initially, publicly available GenAI platforms had an adoption barrier related to prompting (which led to an abundance of online and offline courses on how to craft effective prompts). However, with new models, language has become faster, and conversations are now more intuitive, removing this additional barrier.

[3] ”Will AI Impoverish Us Intellectually?”, April 22, 2024. L’IA ci impoverirà intellettualmente? – by Alessio Mazzucco

[4] “Prolegomena to the Manifesto of Pop Management 18 – Pop Organization.” Opinion piece by Alessio Mazzucco, Nova24, June 24, 2024. Le Aziende InVisibili | Prolegomeni al Manifesto del Pop Management 18 – Organizzazione Pop. Opinion Piece di Alessio Mazzucco

[5] AI at Work Is Here. Now Comes the Hard Part, Microsoft and LinkedIn, 2024 Work Trend Index Annual Report, May 8, 2024.

Author

Alessio Mazzucco

18 February 2025

18 February 2025